|

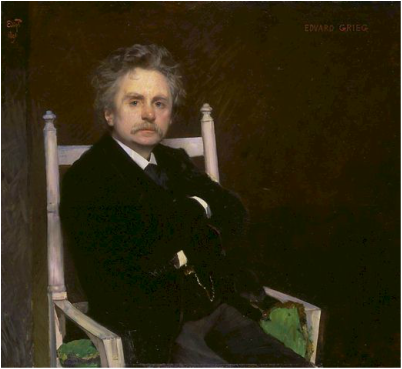

We are too comfortable with Grieg. He is, after all, the composer of the concerto and Peer Gynt and the Lyric Pieces. His music accompanies so many of the movies and TV programs we grew up watching. He has something of the Mozart cliche of "too hard for beginners but too easy for professionals," but without the daunting genius. He is Victorian in the most pejorative sense of the word, and bourgeois, and complacent.

But this is not the Grieg his friends knew, the man of an "agonized longing for light and sun," the Grieg that earned the ire of Debussy through his outspoken criticism of the French government's handling of the Dreyfus Affair. This is not the composer held in the highest regard by Brahms, Liszt, Delius, Ravel, Rachmaninoff, Vaughan Williams, and Bartok, and of whom Tchaikovsky wrote: "What warmth and passion in his melodic phrases, what teeming vitality in his harmony, what originality and beauty in the turn of his piquant and ingenious modulations and rhythms, and in all the rest, what interest, novelty, and independence!" And if we're honest, this is not the Grieg that is in his music. If we perform it for all that’s in it, we find not comfort, but opposition. There really is a scream in his music. He was a man of great division, and the cozy portrait of the composer retreating to his summer villa to write is in fact at odds with very much of the true Grieg; his on-again, off-again cultivation of this image is just one contradiction of a man caught between a romantic and fantastic notion of the folk and a struggle towards the cosmopolitan. Grieg was plagued by self-doubt, depression, marital woes, chronic ill health, and an overwhelming fear that maybe this time it really would be that "the hills had nothing left to tell me." Isn't there something incongruous about his home Troldhaugen? Doesn't its artifice in the context of the fjords and mountains seem at odds with a composer who espoused so much the native music of the land? |

Somewhat analogously, Grieg's early artistic struggle was how to force his musical impulses into the lessons he learned in Leipzig. Once he stopped trying to make them fit into the German molds, however, they bloomed in the form of his greatest achievements — Haugtussa, the Slåtter, the four hymns. It's not that he had never focused his style in his earlier work — it was just inconsistent. The Ballade, Den Bergtekne, and the G minor string quartet are masterpieces from twenty years earlier, and throughout his career the songs are extraordinary. Bergliot has as much 'realism' in it as anything Musorgsky ever wrote.

But it was the late works that paved the way for the twentieth century in a way that is too rarely acknowledged. Grieg is in many ways the founder of impressionism, barbarism, and the bardic impulse of Sibelius. His harmonic sensibility was perhaps his greatest asset as a composer. He claimed it arose from the "undreamt of harmonic possibilities" of Norwegian folksong. Ravel said he never wrote a piece without being influenced by Grieg, and when Delius said to him "modern French music is simply Grieg plus the prelude to the third act of Tristan," Ravel replied "You are right," adding, "we have always been most unjust towards Grieg." To my knowledge, Grieg was the first composer to use the piano as a percussion instrument, instructing portions of the Slåtter to be played "with maximum power." This work — a cycle of Hardanger fiddle transcriptions — was immensely popular in Paris, where the avant-garde applauded 'le nouveau Grieg.' Bartok was a student there at the time. In 1911 he wrote Allegro barbaro; the following year he visited Norway and returned with a Hardanger fiddle. There is aggression and fury, if not sheer violence, in much of Grieg's music. There is incredible spatial tension in his work. He plays with distance and echoes, and with echoes as shibboleths of memory. He blends and confuses and literally enchants in an inimitable Nordic way — being lost in the mountains is his inheritance from Norse myth and fairytale, and from Ibsen, and from the thousands of years of tradition in between. Grieg's music is complex but reticent; it is understated like his people. This is the true folk idiom in his music: not mimicking a Norwegian tune or two, but singing the Norwegian personality. Listen for the breadth, the humor, the torment; listen for the shy and the grandiose. And let Grieg shock us again. |